Pop Art emerged at a moment when the world was changing faster than art could keep up. After World War II, society entered a new visual era television screen flickered in living rooms; advertisements filled streets, and mass-produced images became more influential than paintings in galleries. Pop Art was the first movement to treat this reality seriously. Instead of rejecting popular culture, it examined it with clarity and precision.

Art critic and curator Lawrence Alloway, who first introduced the term, explained that Pop Art was rooted in “mass communications, especially visual ones,” recognizing that modern culture was shaped not by elite symbols but by images consumed daily.

Why Pop Art Became Inevitable?

In the 1950s, dominant movements like Abstract Expressionism focused on personal emotion and inner psychological states. These works were powerful but increasingly disconnected from how people experienced the world. While art explored the subconscious, society was learning how to desire through advertising and media.

Pop Art arose as response to this gap. It asked a radical question: Why shouldn’t art reflect the imagery that shapes everyday life? This shift was not about making art simpler it was about making it more honest.

The Power of the Ordinary Image

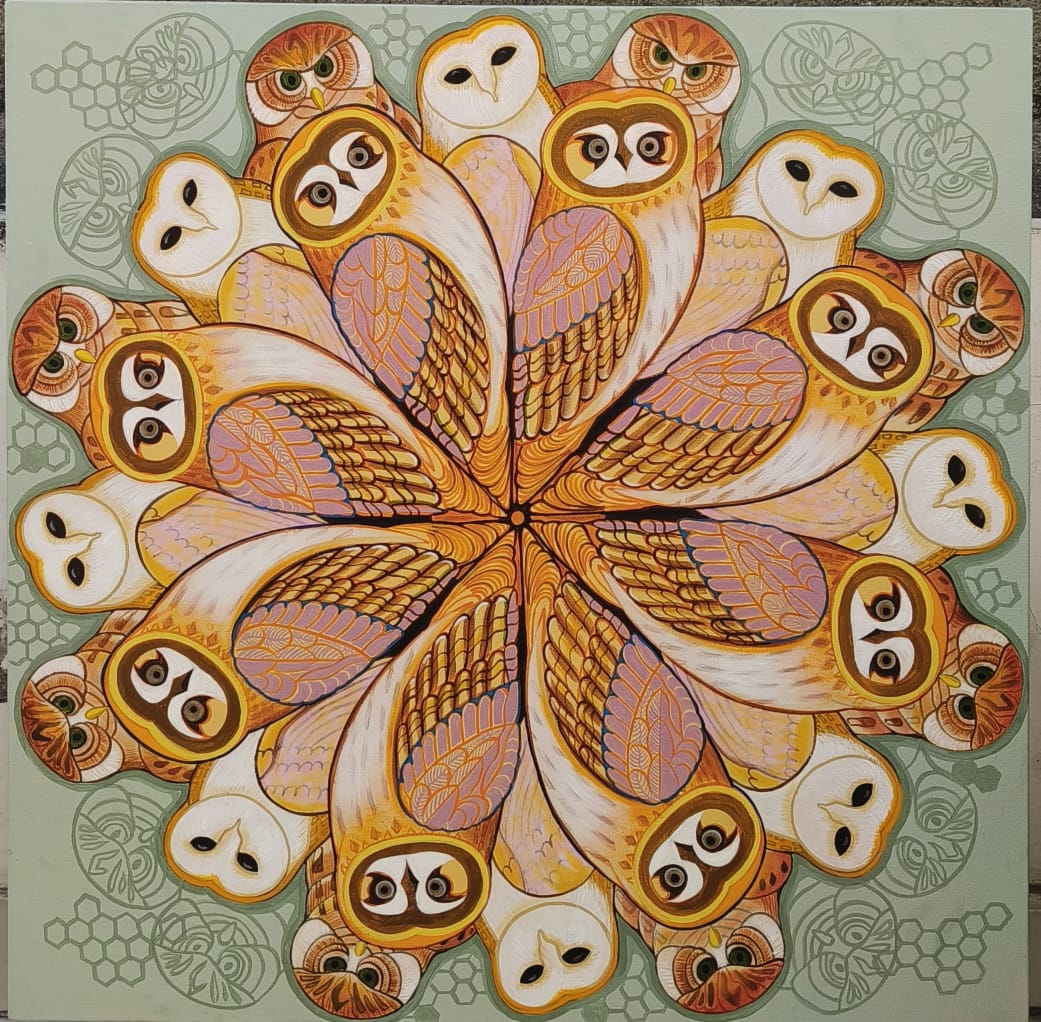

Pop artists deliberately chose familiar subjects: soup cans, comic strips, movie stars, packaging, targets. These images required no explanation because they were already embedded in public consciousness. By relocating them into galleries, artists stripped them of function and forced viewers to look again. Alloway described Pop Art as acknowledging “a faith in the power of images,” emphasizing that these visuals already held meaning before artists touched them. Pop Art didn’t invent significance; it revealed it.

When the Streets Spoke Back: Graffiti as Pop Art’s Loudest Evolution

Graffiti represents one of Pop Art’s most radical transformations where mass imagery escaped galleries and returned to public space. Rooted in repetition, bold symbols, and instantly recognizable visuals, graffiti shares Pop Art’s core language but adds urgency and resistance. Artists like Keith Haring blurred the line first, using subway walls as both canvas and communication system, while later figures such as Jean Michel Basquiat, Shepard Fairey, and Banksy turned street imagery into global symbols. Graffiti driven Pop Art doesn’t ask for permission or contemplation; it demands attention in the same visual environment as advertisements and billboards. By occupying walls, streets, and urban surfaces, graffiti based Pop Art reclaims public space from corporate imagery and reminds us that visual culture isn’t just consumed; it can be challenged, interrupted, and rewritten by anyone willing to leave a mark.

Repetition and the Logic of Mass Culture

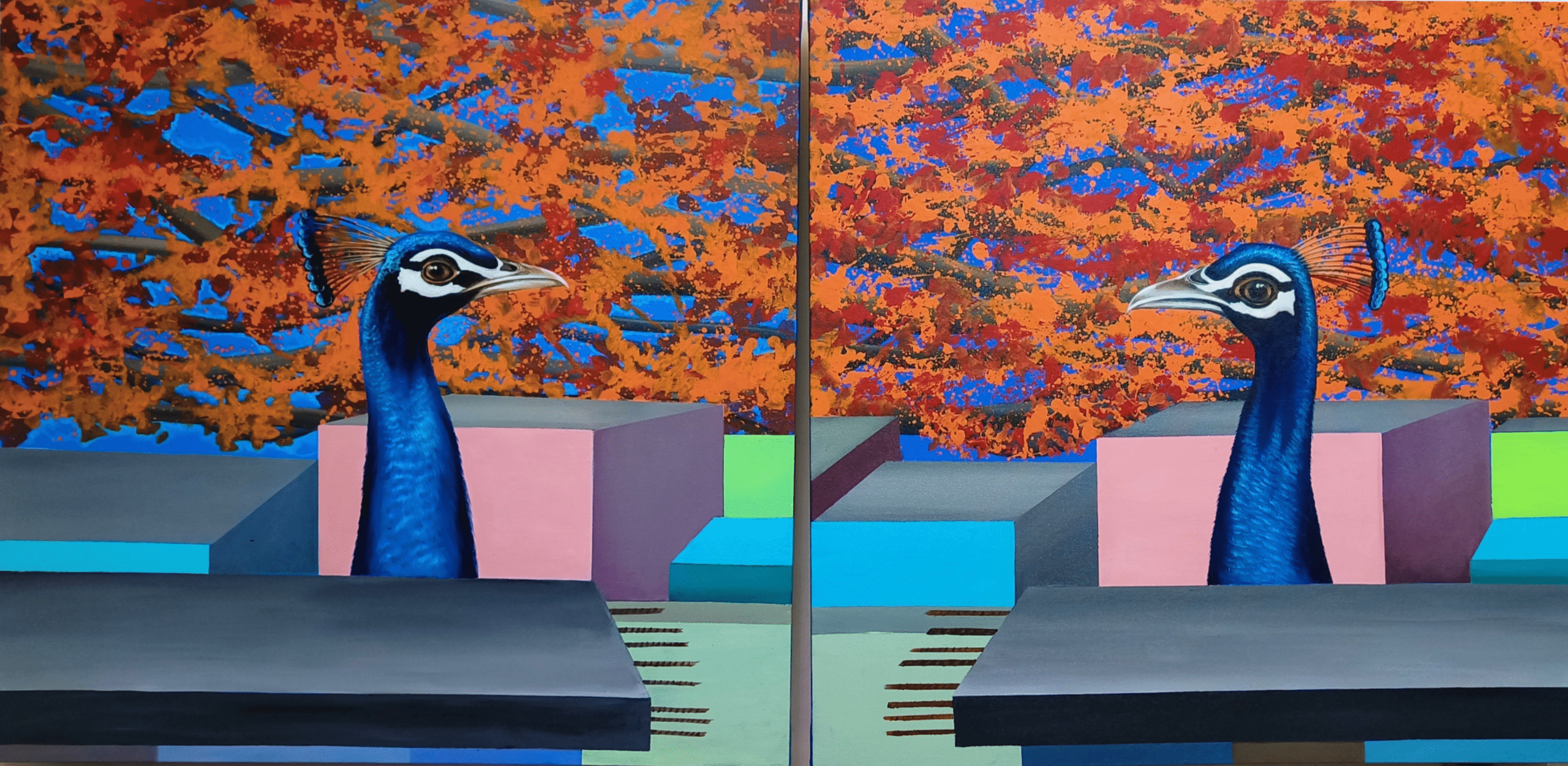

One of Pop Art’s most important strategies was repetition. Images appeared again, echoing how advertising and media operate. Repetition removes emotion and replaces it with familiarity. Pop Art made this process visible. Seeing the same image multiple times encourages viewers to recognize how easily meaning becomes automatic. This was not decoration it was critique through exposure.

Britain vs America: Two Ways of Seeing Pop

Pop Art began in Britain, where artists encountered American consumer culture as something imported and slightly alien. British Pop Art was analytical, ironic, and cautious. It examined advertising as a system rather than a celebration. When Pop Art reached the United States, it became louder and more direct. American artists embraced scale, bold color, and mass production, reflecting a society already immersed in consumer culture. The movement didn’t change its environment did.

The New Faces of Pop: Artists Redefining the Movement Today

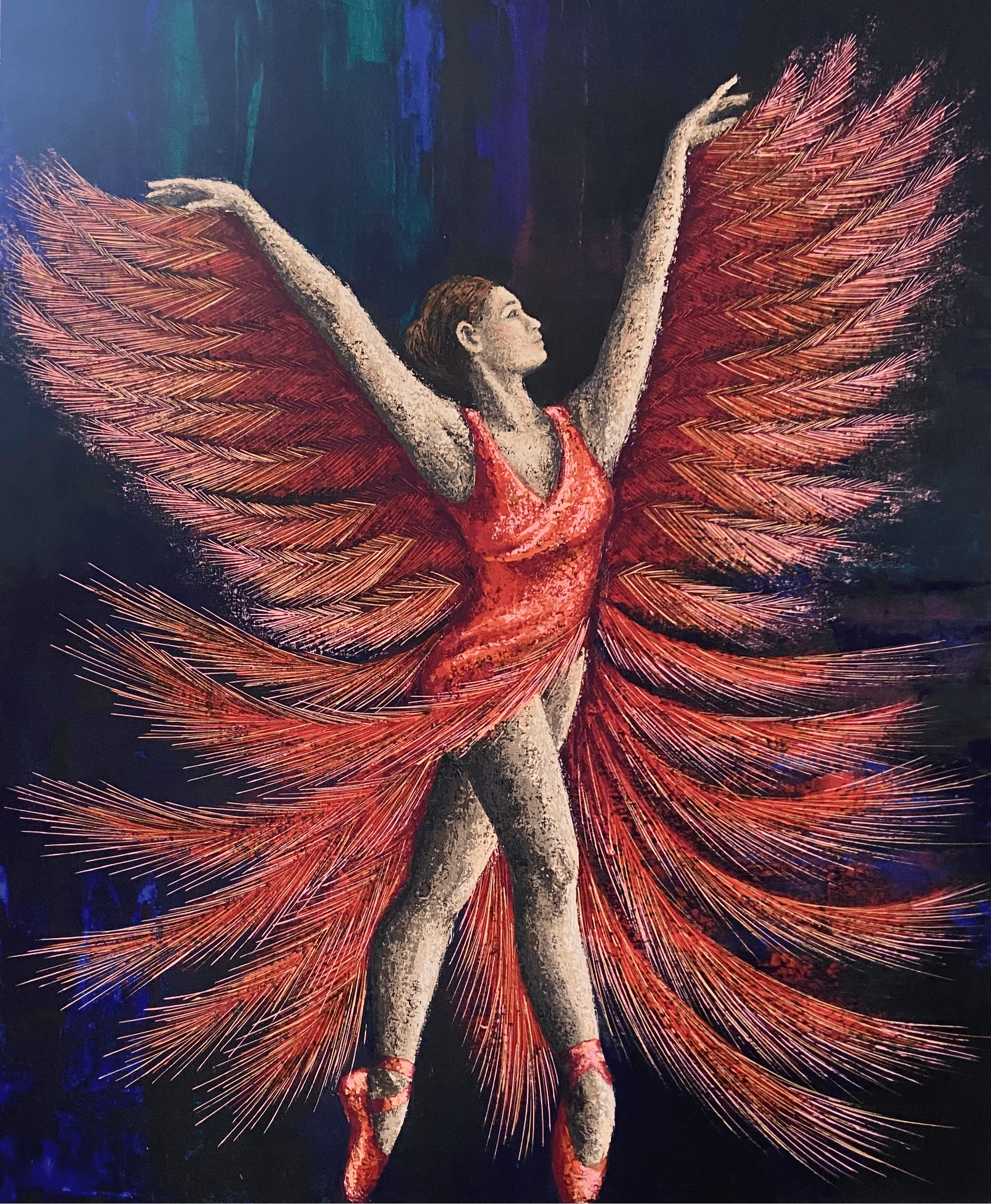

Pop Art didn’t end with Warhol, it quietly transformed. Today’s Pop artists are less concerned with celebrity worship and more focused on how images manufacture identity in a digital, screen-saturated world. Artists like Christine Wang translate internet memes and online irony into sharp, self-aware paintings that reflect how humor has become a coping language for modern life. KAWS, one of the most influential Pop figures of the 21st century, reworks cartoon imagery into emotionally ambiguous icons, revealing how mass-produced characters can carry real psychological weight.

Takashi Murakami merges fine art, commercial design, and Japanese pop culture, showing how art now circulates freely between galleries, fashion, and global branding. Meanwhile, Shepard Fairey and Banksy use instantly recognizable visual language to critique power, media, and control, proving that Pop imagery can still function as political resistance. Artists like Daniel Arsham, who reimagines familiar pop objects as eroded “future relics,” push the movement further suggesting that even our most obsessive images are temporary. Together, these artists demonstrate that contemporary Pop Art is no longer about celebrating mass culture; it is about examining how deeply images shape desire, memory, identity, and belief in the modern world.

Experience Pop Art Beyond the Surface

Pop Art is best understood not through definitions, but through direct experience. When you stand in front of a Pop artwork, familiar images begin to feel unfamiliar and that shift is the point. These works ask you to slow down, look closer, and reconsider the visual world you move through every day. At Elisium Art, our Pop Art collection brings together iconic influences and contemporary voices that continue this conversation. Each piece is chosen not just for its visual impact, but for the ideas it carries about culture, identity, repetition, and modern life.

If Pop Art has ever made you pause, smile, or question what you’re seeing, we invite you to explore the collection and discover the artworks that speak back to the world we live in today.

Escrito por

Manasvi Vislot

Manasvi Vislot is an India based creative storyteller at Elisium Art. She blends global art trends with strategic digital insights, crafting content that connects readers with the evolving world of contemporary, digital, and cultural art. With her refined eye for aesthetics and a passion for making art accessible, Manasvi creates narratives that highlight the artists, ideas, and innovations shaping today’s creative landscape.