Pop Art isn’t a single story. It began as a playful critique of mass culture in the 1950s and 1960s, exploded into mainstream art markets, and later returned in the 1980s with new urgency, political edge, and stylistic reinvention. Where early Pop celebrated immediacy and everyday imagery, later generations rewrote the movement, melding irony, critique, and spectacle into a global visual language that still resonates today.

The 1960s Boom: Image, Celebrity, and the Mass Audience

By the 1960s, Pop Art had become a cultural force. Artists like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenburg borrowed imagery from advertising, cinema, and newspapers to challenge traditional ideas of high art. Instead of metaphors or personal expression, they used familiar icons, such as soup cans, comic strips, and movie stars, to reflect the world as it actually appeared on television screens and billboards.

Warhol’s fascination with celebrity was a key part of this expansion. His iconic 1964 screenprint Shot Sage Blue Marilyn became a meteoric example of how Pop Art could dominate the art market; in 2022, it sold at Christie’s for approximately $195 million. This singular number tells us two things: first, how deeply Pop Art entered the consciousness of collectors and institutions; and second, how dramatically the market now values imagery once dismissed as banal. As curator Hans Ulrich Obrist observed, “Pop Art didn’t just reflect popular culture, it anticipated how images would dominate everyday life.”

The early boom wasn’t limited to Warhol. Prints and paintings by Pop artists were frequently auctioned in the decades that followed. For example, Christie’s reported over 8000 visitors and 500 registered bidders for a series of Pop Art sales in 2014, a testament to the enduring global appetite for the movement. By turning everyday visuals into fine art, 1960s Pop Art reshaped what galleries showed, what critics discussed, and what audiences collected. It blurred distinctions between art and commerce, celebrity and anonymity, production and repetition.

The 1970s: From Celebration to Interpretation

Pop Art’s dominance began to shift in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Its initial shock value diminished as the imagery it used became increasingly familiar. Artists and curators began to ask new questions: Was Pop just about surface spectacle? Or could its logic be extended to critique power, politics, and identity? This period saw a gradual move toward what would later become Postmodernism. Pop’s flat surfaces and repetition influenced conceptual art, performance, and other emerging disciplines. The bright, seemingly celebratory masks of mass culture began to look more like tools of ideological construction. Artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring bridged this transition into the 1980s, fusing Pop’s visual strategies with political urgency, identity exploration, and street culture. Their work adapted Pop’s visual language to comment on race, economics, and social structures far beyond commercial logos and celebrity portraits.

The 1980s Edge: Bigger, Darker, and More Political

By the 1980s, Pop Art had returned, but not unchanged. This new wave, sometimes called Neo-Pop or Post-Pop, was louder, more aggressive, and often explicitly political. It drew from the first wave’s visual vocabulary but added new layers of critique. Artists like Kenny Scharf integrated Pop imagery with street art and science fiction tropes, reflecting Cold War anxiety and media saturation. Meanwhile, collaborations between Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, such as the 1985 painting Zenith, which has sold in the millions, show how the movement’s stakes had shifted; it was no longer just about consumer culture, but about art’s relationship to power, identity, and urban experience. This 1980s resurgence also saw a broader embrace of color, pattern, and spectacle, traits that influenced design movements such as Memphis Design, which brought Pop’s energy into furniture, interiors, and architecture.

Curator Voices on Pop’s Evolution

Pop Art’s transformation wasn’t accidental; it was documented and theorized as it happened. Art historian Hal Foster wrote, “Pop Art revealed that culture itself had become a system of images, endlessly circulated and consumed.” This insight helps explain why Pop Art didn’t fade: the world it described did not go away; it expanded. These voices help us see Pop not just as a historical style, but as a framework for understanding how art and everyday imagery interact.

The Pop Art market reflects this evolution. According to auction data, Pop Art prints and works have seen strong sales: in 2022 alone, around £36 million worth of Pop and Post-Pop prints were sold through auction houses, a sign of continuing global demand. Even modest Warhol prints regularly exceed high estimates; for example, Jacqueline Kennedy II more than doubled its expected price at auction, selling for £52,920 in London. This traction isn’t limited to the giants of the 1960s. Later and contemporary Pop-influenced artists often appear in broader market reports, reflecting how the movement’s visual language remains active in collecting and exhibition contexts.

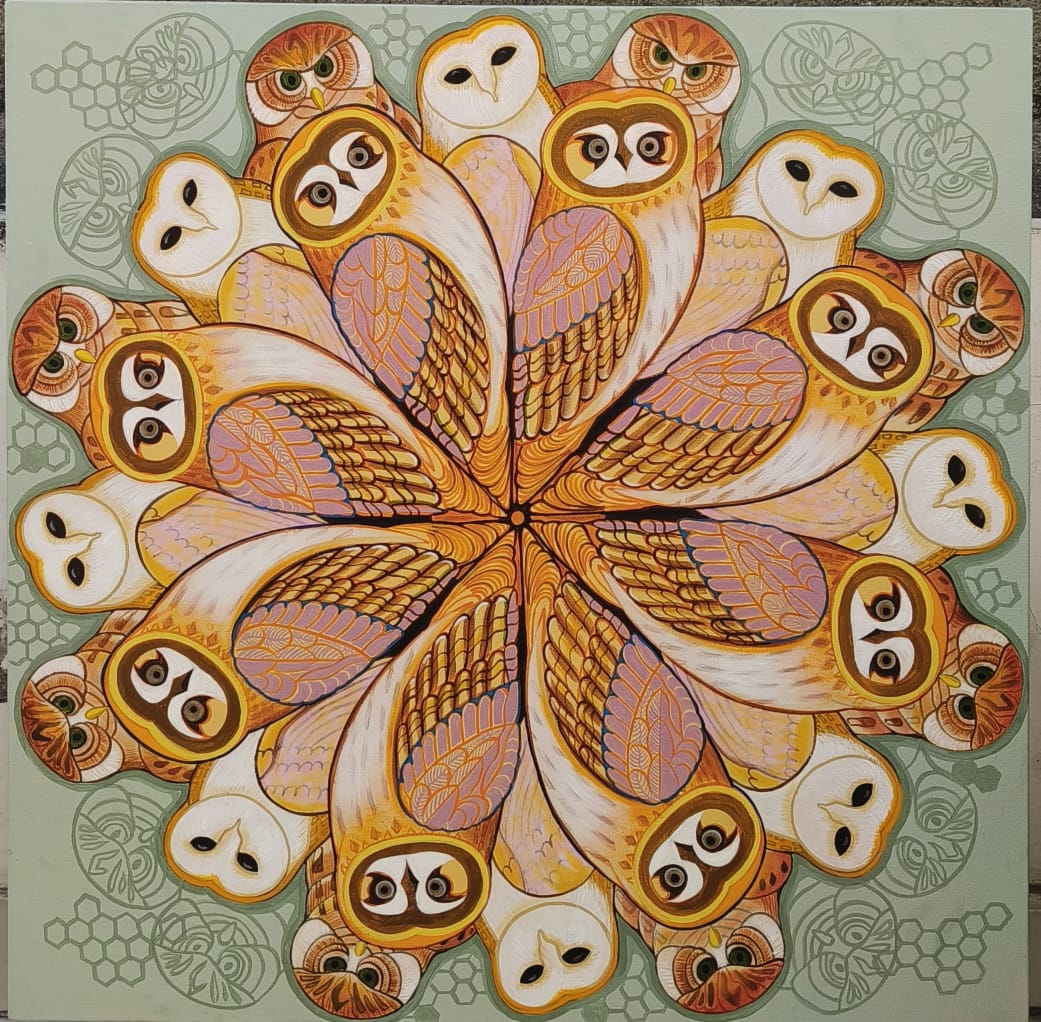

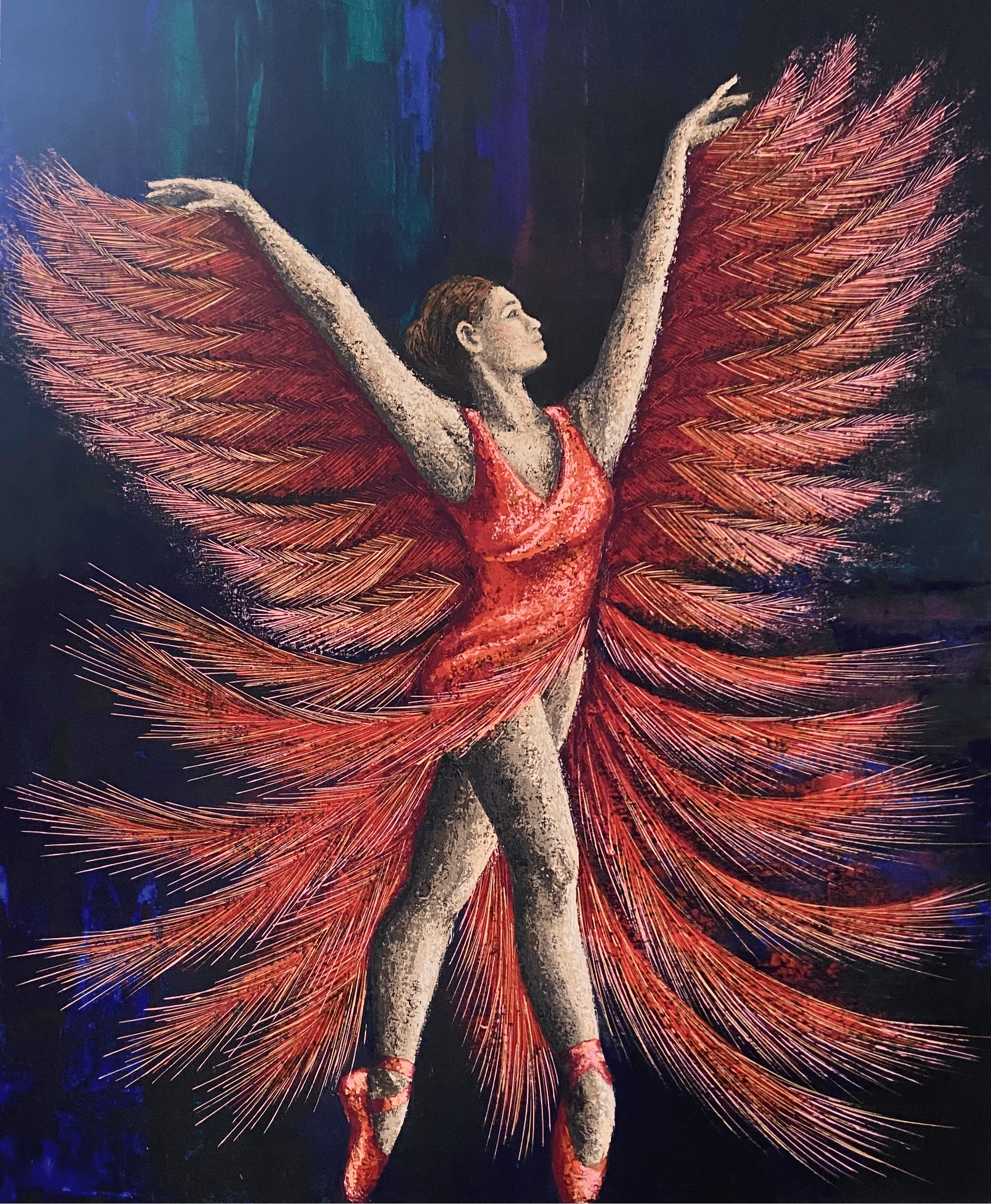

Pop Art’s Influence on Contemporary Creators

The legacy of Pop’s reinvention in the 1980s continues to shape artists today. On Elisium Art, contemporary painters engage with this legacy in fresh and meaningful ways. Catalina Cayon’s Un Humano Nos Está Mirando, for example, uses vibrant color, figurative distortion, and layered symbolism to examine human presence and perception in a world saturated with signs. Explore it here: Her work extends Pop Art’s blend of visual familiarity and psychological depth into our present context.

Escrito por

Manasvi Vislot

Manasvi Vislot is an India based creative storyteller at Elisium Art. She blends global art trends with strategic digital insights, crafting content that connects readers with the evolving world of contemporary, digital, and cultural art. With her refined eye for aesthetics and a passion for making art accessible, Manasvi creates narratives that highlight the artists, ideas, and innovations shaping today’s creative landscape.