Pop Art’s spirit didn’t die with the 1970s. It transformed. In the 1990s and 2000s, the world changed beneath a visual culture driven by branding, globalization, and digital tools, and artists reshaped the language of image itself. What began as commentary on consumer goods became a global visual lexicon, bridging continents, aesthetics, and markets. In this era, images became not just something artists used; they became the very way culture spoke.

Branding, Globalization & the Art of the 1990s

By the 1990s, imagery functioned less as decoration and more as currency. Logos and brands shaped identity, fashion houses turned symbols into status markers, and billboards became cultural statements. Contemporary artists absorbed this visual language, using familiar signs not as surface references but as core elements of meaning. This shift mirrored a larger global change: companies were no longer local but international, and their imagery was universally recognizable. Art began operating in the same visual economy as advertising, fashion, and mass culture, setting the stage for post–Pop Art practices.

Damien Hirst emerged as a defining figure of this moment. Though not a traditional Pop artist, he carried forward Pop’s engagement with recognizable imagery and mass appeal. Rising through the ranks of the Young British Artists in the 1990s, Hirst quickly became synonymous with global collector culture. His auction debut in June 1995 marked the beginning of a market ascent that culminated in significant sales, including Lullaby Spring (2002), which sold for approximately $19.2 million at Sotheby’s. Curator Robert Storr once observed that Hirst’s work “merged imagery with market logic, making art itself a global communication system,” capturing how images became vehicles of value rather than mere content.

At the same time, art institutions were undergoing their own transformation. Museums expanded their scope beyond national narratives, while international biennials multiplied from Venice to Istanbul to São Paulo. Visual culture was no longer regional; it was global. In this context, Pop Art’s legacy extended beyond style, shaping the very structure through which contemporary art was produced, circulated, and understood.

Digital Tools Change Visual Culture

The rise of digital tools in the 1990s and early 2000s further altered how images were made, seen, and circulated. Adobe Photoshop, introduced in the early 1990s, gave artists unprecedented power to manipulate images. Suddenly, what used to take days in a darkroom could be done in moments on a computer. It wasn’t just a technical convenience; it changed the way we think visually.

Artists could now layer, blend, and remix imagery faster than ever before. By the late 1990s, the internet had grown into a global network where visual content spread instantly. A meme, a remix, a scanned collage, all became part of a new digital vernacular. These tools did more than democratize image creation; they reshaped our expectations of what images could do. Prema Murthy, an early digital artist active in the 1990s, explored these intersections of technology and culture. Her work, including pieces like Bindigirl and Mythic Hybrid, used early digital aesthetics and online platforms to question identity, race, gender, and globalization. These experiments were not about novelty. They were early proofs that art could be natively digital, not just transferred into digital form.

By the early 2000s, the lines between “fine art” and digital image culture had blurred for good. Artists no longer needed paint or canvas to be significant. A JPG, a glitch, or a remixed logo could carry as much meaning as any traditional medium.

Pop Art Without Calling It Pop Art

As the art world entered the late 1990s and 2000s, movements inspired by Pop Art’s logic began popping up worldwide, even if they no longer used the term. Three figures illuminate this transformation:

Damien Hirst

Though not marketed strictly as a Pop artist, Hirst’s global visual brand, from his spot paintings to medicine cabinets, echoes Pop’s engagement with serial imagery and market dynamics. His works have dominated auction headlines for decades, and his peak auction impact was arguably the “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” sale in 2008, where 218 of his pieces brought in around £111 million (approximately $200 million), a record for a single-artist auction.

Takashi Murakami

Murakami’s influential Superflat movement mixed pop culture, anime, and fine art into a new postmodern vernacular that spoke across East and West. His refusal to separate high and low cultureand his embrace of commercial collaborations show how Pop’s collapse of hierarchies became global.

KAWS

Born Brian Donnelly, KAWS began in street culture, subverting billboards and urban signs before gaining global acclaim. His Companion figures and limited-edition sculptures merge the visual language of cartoons with fine-art contexts. Today, KAWS shows in major museums and commands significant market interest as a bridge between street art, design, and gallery culture.What’s important here is not that they look like Pop Art. It’s that they use imagery — corporate, media, animated, technological as a universal language. The imagery itself becomes content. The questions become global.

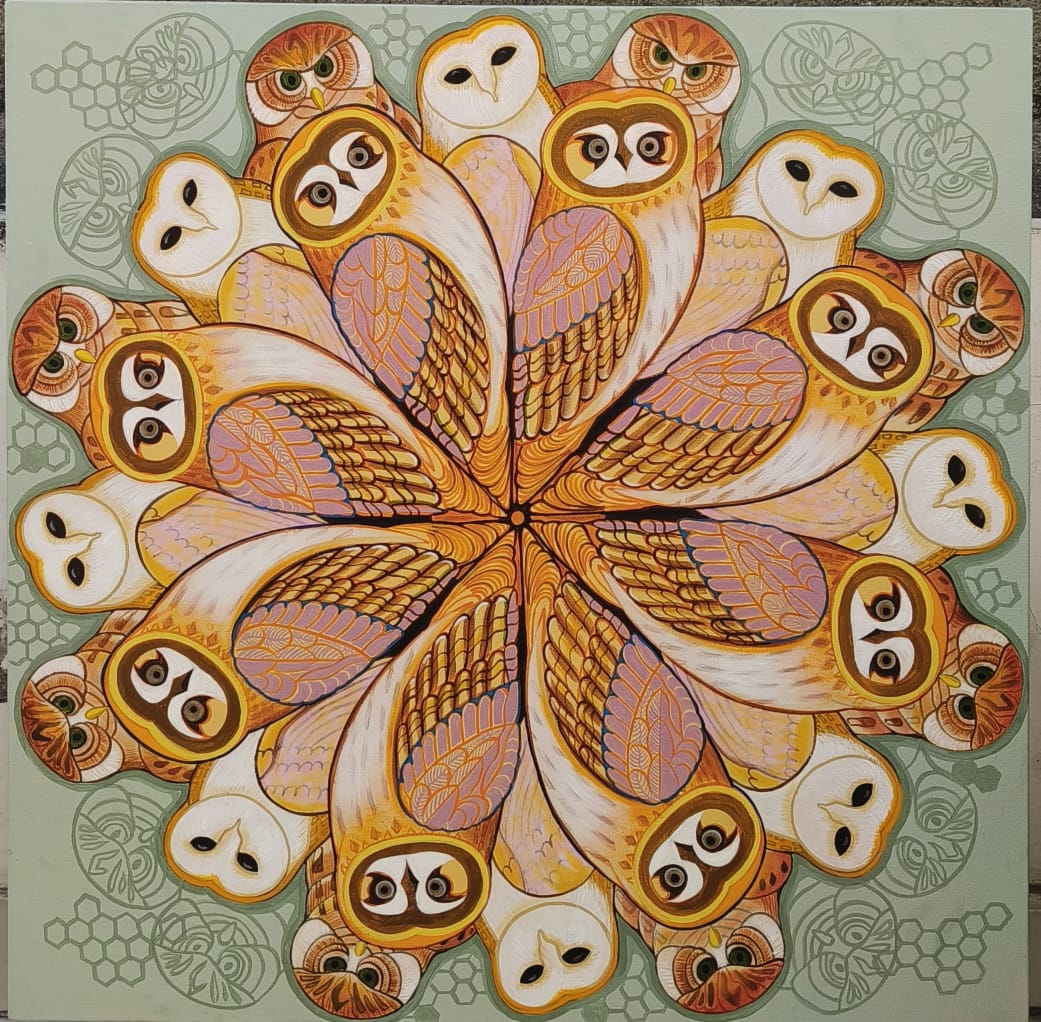

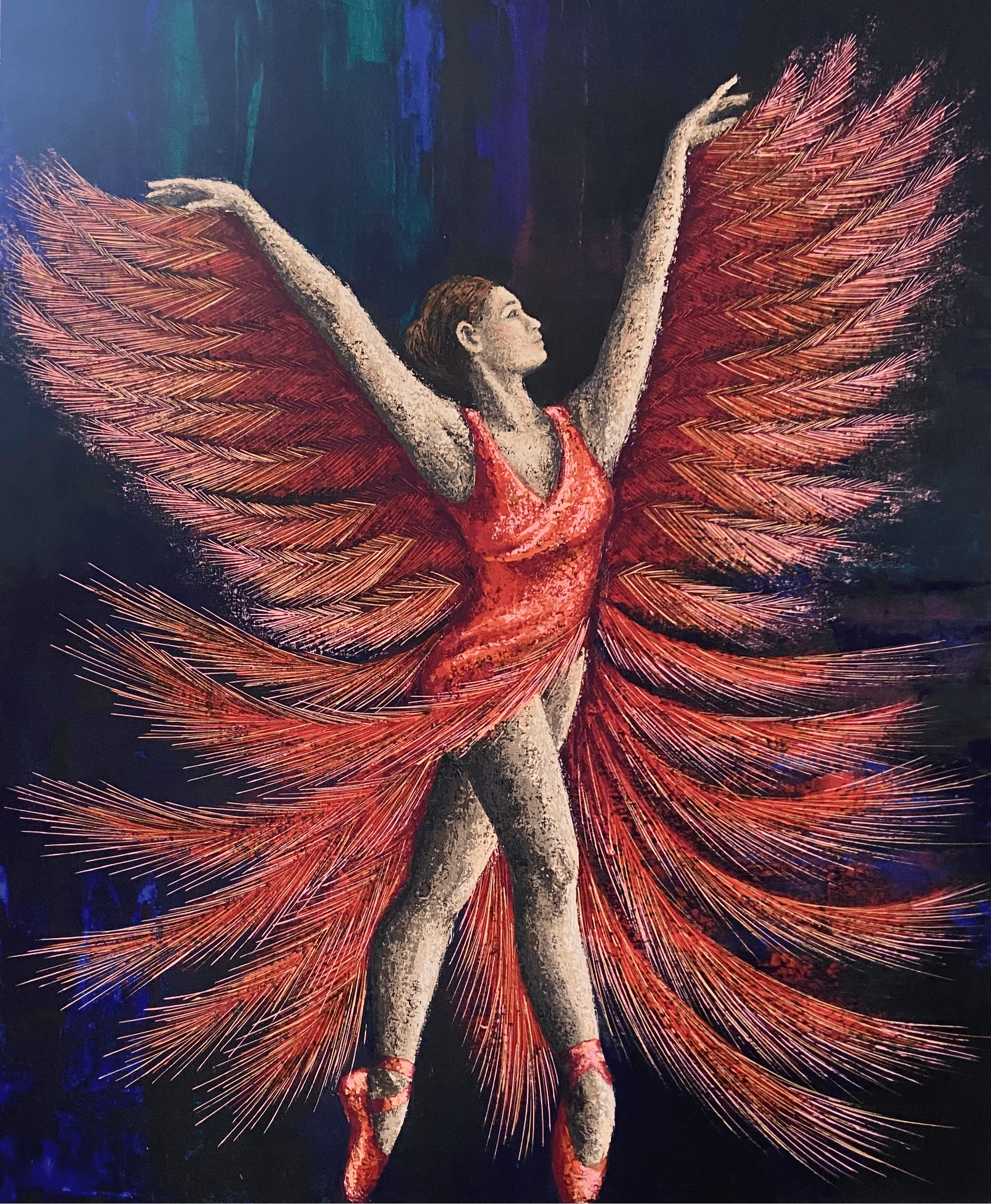

Contemporary Threads and Collaborative Futures

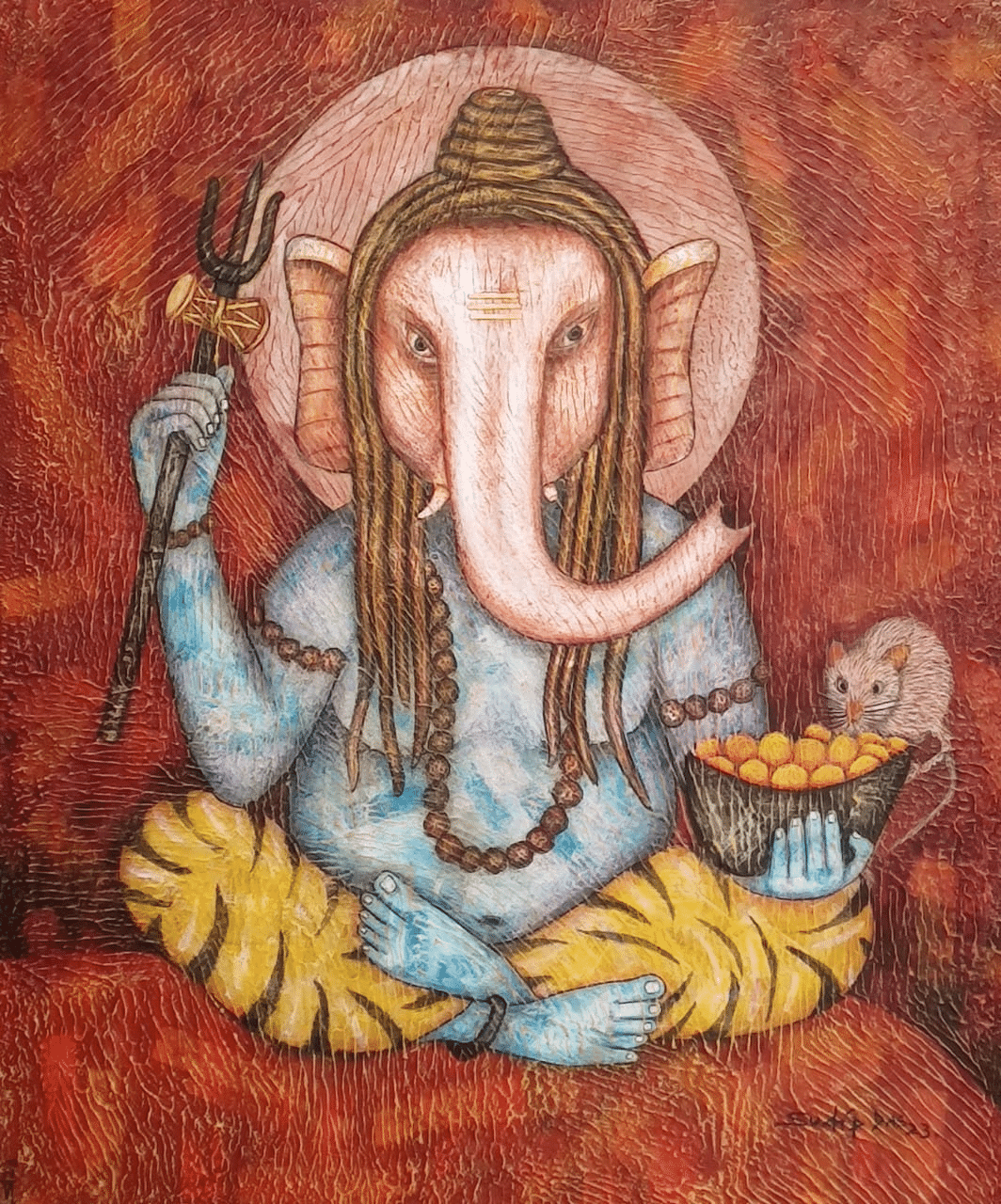

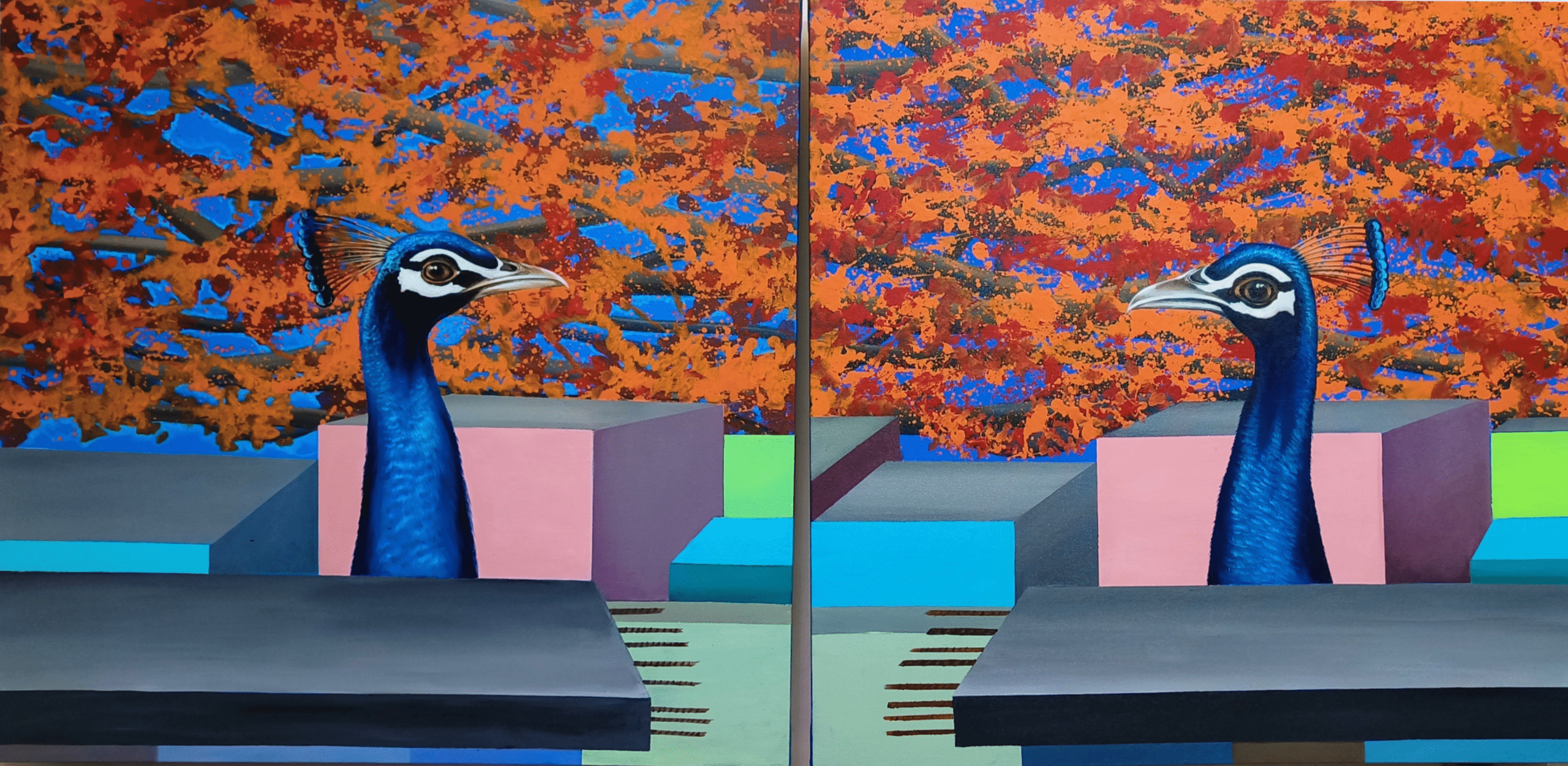

The artists of the 1990s–2000s rewrote the terms of visual engagement, and that legacy is alive in artists today, including those featured on Elisium Art. For example, Elephant by Carolina Piedrahita blends symbolic visual language with expressive form to examine presence, memory, and narrative in a visual culture shaped by global communication.Piedrahita’s painting doesn’t wear Pop Art’s colors on its sleeve. Instead, it continues Pop’s deeper inquiry: how images communicate meaning, emotion, and identity in a world where the visual is omnipresent.

Escrito por

Manasvi Vislot

Manasvi Vislot is an India based creative storyteller at Elisium Art. She blends global art trends with strategic digital insights, crafting content that connects readers with the evolving world of contemporary, digital, and cultural art. With her refined eye for aesthetics and a passion for making art accessible, Manasvi creates narratives that highlight the artists, ideas, and innovations shaping today’s creative landscape.